Treatment of PVNS

The most commonly performed treatment for diffuse, pigmented

villonodular synovitis is a surgical synovectomy.

Synovectomy simply means removal of the internal joint lining

membrane. Before arthroscopic techniques were available, synovectomy

was performed in an open fashion, with a large frontal incision

literally opening the knee up like a book so that the majority

of the joint lining tissue, which is in the front of the joint,

could be stripped out. Opening up the rear of the knee to remove

the synovial lining in the back of the joint was sometimes done

as a more radical extension of the frontal synovectomy procedure.

These open surgical procedures had serious drawbacks, in that

they were quite painful and often produced major post-operative

morbidity such as joint scarring and stiffness. In addition, as

extensive as these procedures were, every last bit of abnormal

synovial tissue was still not removed. As noted

previously, to perform a genuinely complete surgical synovectomy,

extreme damage to the joint would have to be done because the

knee cartilages (menisci) would effectively have to be removed,

along with portions of the internal (cruciate) ligaments. Only

such radical surgery would allow access to all of the small nooks

and crannies within the knee joint where PVNS tissue can hide.

While not necessarily more effective than open synovectomy, in

most cases a better approach is arthroscopic synovectomy

(see FIGURE 4).

|

FIGURE

4 - When removing PVNS tissue from the knee joint arthroscopically,

a small, motorized tissue resection instrument is introduced

into the knee through a 1/4 inch skin incision, or "portal."

The surgical work is observed by way of an arthroscope (shown

here in the upper right-hand section of the FIGURE), inserted

through another skin portal incision from a different angle.

Each pair of portal incisions (arthroscope and resector instrument)

allows a certain region of the knee joint to be cleaned out,

with a comprehensive synovectomy requiring upwards of six

to eight access portals |

For patients interested in the technical aspects of arthroscopic

knee synovectomy, reprints of my illustrated surgical technique

paper, published in Master Techniques in Orthopedic Surgery,can

be obtained by either writing or e-mailing our Knee and Shoulder

Centers office. Simply stated, the objective of arthroscopic

synovectomy is to remove as much abnormal joint lining tissue

as is technically feasible without damaging the patient's knee

in the process. Properly and meticulously performed, it is

a very lengthy and technically difficult surgical procedure. It

requires mastery of almost every knee access technique ever devised

by arthroscopic surgeons. All of the major internal regions of

the knee joint, in sequence, must be both visualized and accessed

by surgical re-section instrumentation, all the while keeping

the number of access (arthroscope portal) incisions to a minimum

and avoiding unintended neurovascular injury or damage to other

internal joint structures. The surgeon must be comfortable working

in the posteromedial and posterolateral knee compartments (see

FIGURE 5) and have the patience to follow the abnormal

joint lining tissue down into every accessible fold and recess

elsewhere within the knee joint. When PVNS disease afflicts the

cruciate ligaments, the synovial lining membrane of these ligaments

must be carefully and meticulously dissected away (both in the

front and sometimes in back) without damaging the ligaments themselves

(see FIGURE 6).

|

FIGURE

5 - This illustration shows another step during the

course of a comprehensive, internal knee synovectomy. Here,

the arthroscope (left) is being inserted into the posterolateral

(rear, outside) compartment of the knee directly, while the

resector instrument reaches the inner regions of that compartment

indirectly by passing through the inter-condylar notch (center

space of the knee) from the front. When creating surgical

access portals toward the back side of the knee, great care

must be taken not to injure the nearby nerves and blood vessels

leading to the lower leg. In this picture, the critically

important peroneal nerve is seen just beneath the posterolateral

arthroscope access portal. Remember that the surgeon cannot

actually see this nerve at the time the adjacent skin portal

incision is made! He or she must be guided by way of external

landmarks and a sound knowledge of internal knee anatomy. |

|

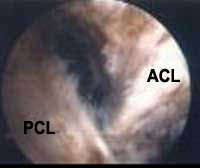

FIGURE

6 - This arthroscopic view demonstrates a patient’s

anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate

ligament (PCL), looking from behind, as the arthroscope

has been inserted by way of a posterior-medial portal access

site. These cruciate ligaments were previously surrounded

by PVNS tissue, which was carefully stripped away, both

in front and in back, by way of arthroscopic instrumentation.

|

|

Clinical experience has generally demonstrated that the more

complete the degree of synovectomy achieved, the lower the recurrence

rate of the disease. However, even with a consummately skilled

surgeon using the most advanced arthroscopic techniques, it is

still impossible to remove every last bit of PVNS tissue in the

diffuse form of the disease. Current surgery is, therefore, limited

to a thorough "debulking"process that falls short of

total resection. The surgeon attempts to achieve the greatest

possible debulking effect in order to minimize the recurrence

rate,while still leaving the patient with a functional knee afterwards.

Why the disease does not recur in all cases, following what

we know to be less than a 100% synovectomy, is unknown. Diffuse

PVNS is truly a strange disease that appears for uncertain reasons

and may also completely exit a patient's life following treatment,

even though by definition that treatment is known to have been

incomplete. If there has been any common etiologic

(causal) thread in many of the PVNS patients I have treated, it

has been that they had some episode of knee trauma in their past

that caused bleeding within their knee joint. Whether a brief

exposure of a synovial joint to the iron-based hemoglobin pigment

released by degrading red blood cells can actually cause PVNS

has never been proven and at this point must be relegated to personal

speculation.

Other means of treating pigmented villonodular synovitis include

radiation beam therapy and radio isotope synovectomy. In the latter

procedure a liquid, radioactive isotope is injected into the knee

joint, subjecting the synovial lining to radiation treatment.

This is an uncommon treatment that in the past has generally been

reserved for difficult cases of PVNS that have recurred following

a prior surgical synovectomy. Very few medical centers in the

United States even offer such treatment, which is usually done

under carefully controlled conditions in research protocols. Either

form of radiation therapy can also be used as an adjuvant (additional

or back-up) treatment following a surgical synovectomy.

If PVNS remains uncontrolled, over a period of years the patient's

knee joint surfaces may gradually become destroyed, leading to

a need for radical joint resection and replacement by prosthetic

components ("total knee replacement" surgery). The initial

radical resection stage of such a procedure allows relatively

complete exposure inside the joint and thus an unusually complete

surgical synovectomy. This often leads to a final cure of the

disease, but the original knee joint has been lost forever.

In this author’s experience, a recurrence of diffuse PVNS

following an initial synovectomy procedure is still worth treating

with another attempt at a comprehensive arthroscopic synovectomy,carried

to the most radical extent that is feasible. In some cases unusual

measures such as resecting the soft tissue from behind the posterior

cruciate ligament must be performed, as that is a site where nests

of PVNS tissue may form and even begin to reach outside the

confines of the knee capsule. Resection of such extra capsular

(outside of the knee joint proper) PVNS tissue with an arthroscope

is an extremely tricky process, particularly in the posterior

regions of the knee joint where the major neuro vascular structures

that feed the lower leg and foot are located. Most scientific

articles and book chapters on PVNS do not even discuss the fact

that PVNS tissue can occasionally escape the confines of the joint

cavity to invade soft tissues outside of the capsule. While it

is well known that PVNS tissue can actually grow into the femur

or tibia itself, apparently by following vascular (blood vessel)

channels into the bone, it is less commonly appreciated that PVNS

tissue can grow along small, trans-capsular passage ways leading

out of the knee joint cavity to form masses of tissue in external

regions. Two such regions are known as the lateral popliteus recess

and the medial gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa (see

FIGURE 7). Extra-capsular extensions of PVNS disease are

best detected pre-operatively by way of MRI scanning with special,

hemosiderin-weighted imaging techniques. If identified, such extra-articular

nests of PVNS tissue are usually best resected by way of localized,

open surgical exploration, leaving the intra-articular PVNS tissue

to be resected by arthroscopic means.

|

FIGURE

7 - This MRI scan shows a cross-sectional, side view

of a knee. The rounded femoral condyle sits atop the flat

upper tibia. The front of the knee is to the right and the

back of the knee is to the left. The arrow points to an accumulation

of PVNS tissue outside of the knee joint, filling up a natural

pouch or space known as the gastrocnemius-semimembranosus

bursa. The PVNS tissue appears black in this MRI study. If

you look within the knee joint cavity in front of the femur,

you will see additional, dark PVNS tissue, in a more typical

location. This patient was treated with a comprehensive arthroscopic

synovectomy inside the joint followed by excision of the extra-articular

mass of PVNS tissue (arrow) using an open, posteromedial skin

incision and exploration. Six years after surgery, this patient

was symptom free and an apparent cure. |

Resolution of the disease process is usually heralded by an elimination

of the patient's prior recurrent knee effusions (excess joint

fluid accumulations). Post-operative MRI scans are extremely

difficult to read because of scar tissue artifact. If at some

point excess knee joint fluid begins to return, this is suggestive,

but not definitive proof of, recurrence. If long-lasting, the

presence of recurrent fluid suggests the need for a follow-up

MRI scan and an arthroscopic re-inspection of the joint.

For recurrent disease, a combination of repeat synovectomy,

possibly followed by irradiation or radioisotope, adjuvant

synovectomy, can be considered. Individual consultation between

the patient and the subspecialists at those few medical centers

offering the latter technique is required to determine whether

the patient is a potential candidate for this treatment.

|